When it comes to stretch fabrics in apparel, two common knit types stand out: tricot fabric and jersey knit. Both are often blended with spandex (elastane) to add elasticity, but they differ fundamentally in how they are made and how they perform. Tricot fabric is a warp-knit textile, while jersey is a weft-knit (or circular-knit) fabric.

This structural distinction leads to notable differences in stretch behavior, weight, drape, breathability, opacity, texture, and durability. Understanding these differences is crucial for designers and manufacturers when choosing the right material for swimwear, activewear, intimates, dance costumes, shapewear, and other applications.

In this article, we define both tricot and jersey knit fabrics, compare their properties (from stretch and recovery to softness and strength), and provide technical guidance – including how to identify each fabric type and practical tips for selecting tricot fabric or jersey knit for specific uses.

What is Tricot Fabric? (Warp Knit Definition)

Tricot fabric is a type of warp-knit textile constructed with yarns that knit in a vertical zigzag fashion along the fabric’s length. In warp knitting (used for tricots), each needle on the knitting machine has its own yarn, forming loops that interlock down the length of the fabric rather than across its width.

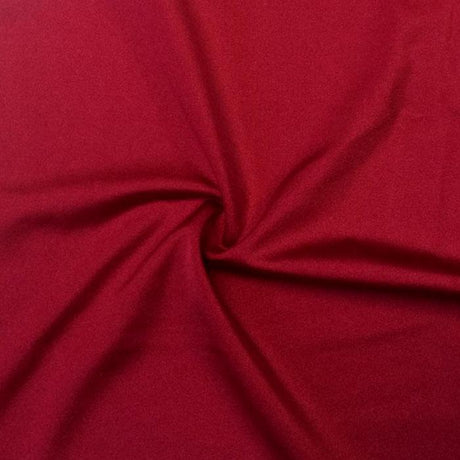

This produces a very stable yet flexible material. Tricot is characterized by having one side that is smooth (the technical face) and another side that is textured with fine horizontal ribs (the technical back) due to the zigzag loop structure. The yarns move diagonally from wale to wale as the fabric is formed, giving tricot a distinctive knit pattern.

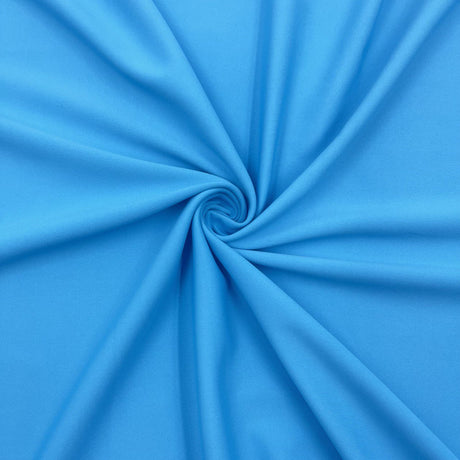

Typically, tricot fabrics are made from filament yarns such as nylon or polyester, often blended with 10–20% spandex for stretch. (Originally, tricots were even made of silk, though modern tricots are usually synthetic.) The use of fine filament fibers gives tricot a silky, smooth touch on the face and a soft, slightly textured feel on the back. Tricot knit fabric is known for its excellent lengthwise stretch and good elasticity, especially when spandex is included.

Yet it remains dimensionally stable, meaning it holds its shape and won’t easily sag or lose recovery. The warp-knitting construction also makes tricot run-resistant – it doesn’t unravel or ladder if cut or if a yarn is broken. This durability and stability are a major advantage of tricot fabric. Because of these properties, tricot is widely used in form-fitting and high-performance garments. You’ll commonly find tricot fabric in lingerie, swimwear, athletic wear, dancewear, and linings, where its smooth feel, stretch, and strength are desired. In summary, tricot is a specialized knit that provides a soft, smooth, and sturdy stretch fabric ideal for many technical applications.

What is Jersey Knit Fabric? (Weft Knit Definition)

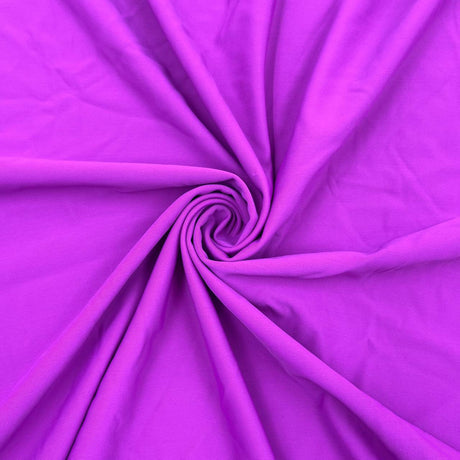

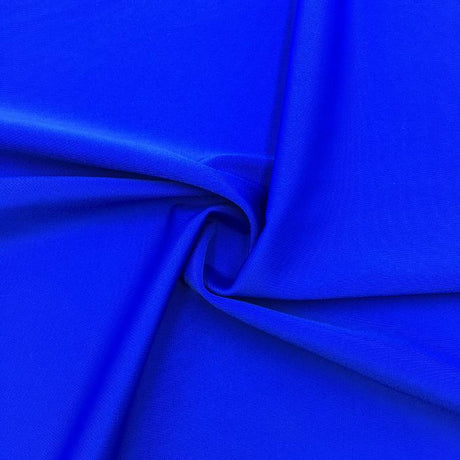

Jersey knit is a weft-knit fabric (often produced on circular knitting machines) made by looping one continuous yarn across the fabric’s width, row by row. Classic single jersey – also known simply as jersey – is constructed with all knit stitches on the face and purl stitches on the back. This gives jersey a “right” side that is smooth with tiny V-shaped knit stitches, and a “wrong” side that shows purl loops (a slightly nubby or textured surface). In other words, the front of a single jersey has fine lengthwise ribs (from the knitted loops), while the reverse side has crosswise rows of loops. (Double-knit jerseys, like interlock, use two layers of loops so both sides appear smooth, but here we focus on the single jersey structure.) Jersey fabrics were originally wool, but today they are made from a variety of fibers – cotton, cotton blends, polyester, nylon, rayon – often with a bit of spandex to increase stretch.

Jersey knit is known for being soft, supple, and very stretchy. The loop structure naturally gives it a good amount of give, especially in the width (horizontal) direction, making it comfortable for close-fitting garments. (A plain cotton jersey without spandex typically has two-way stretch – mostly across the width – but when spandex is added it becomes a four-way stretch fabric, extending both widthwise and lengthwise with excellent recovery.) Jersey is usually a light to medium weight fabric with a fluid drape, which is why it’s so popular for t-shirts, draped tops, knit dresses, underwear, and even bedsheets. The knit structure brings the yarns close together, making jersey fabric generally opaque (no significant light passes through a quality jersey) and breathable, especially when made from absorbent fibers like cotton.

One thing to note about jersey is that its edges tend to curl when cut. Because one side of the fabric has all knit stitches and the other side all purl, there is an imbalance of tension that causes jersey knit edges to roll toward the front or back (for example, a cut edge will curl toward the smooth knit side along the width). This curling is a hallmark of single jersey and can make it a bit tricky to lay out and sew. Jersey can also run or ladder if a stitch is broken, since the one yarn runs throughout each course (row) of the fabric. Despite these quirks, jersey knit remains one of the most common and versatile fabrics in apparel due to its softness, stretch, and comfort. It’s the fabric of choice for everyday knitwear like basic tees, leggings, hoodies (sweatshirt fleece is a type of jersey), and much more.

Structural Differences: Warp Knit vs Weft Knit

The fundamental difference between tricot and jersey starts with how they are knitted. In warp knitting (tricot), multiple yarns are fed in parallel along the fabric’s length (like the warps in weaving), and each yarn forms loops that interlock with loops from adjacent yarns in a zigzag pattern down the length. Every needle on the knitting machine works with its own yarn, creating many loops simultaneously in each course.

By contrast, in weft knitting (jersey), one yarn (or a few yarns) works horizontally across the fabric, forming one loop after another in sequence across the width of the fabric, then moving to the next row. A single yarn can knit an entire row of jersey. This means tricot cannot be made by hand (it requires a warp knitting machine and multiple yarns), whereas jersey weft knits can be hand-knitted (think of the classic knit and purl structure of a sweater) or machine-knit in a continuous spiral on a circular machine.

Because of these construction differences, tricot fabric will not unravel in the same way a jersey can. All weft-knitted fabrics (like jersey) can be unraveled by pulling a cut yarn end in the direction opposite to the knitting – the loops will come out sequentially along the row. In contrast, a tricot warp-knit has interlocked yarns that won’t easily come undone; you generally cannot “unzip” a tricot by pulling a thread.

This is why tricot is called run-resistant or fray-resistant – it doesn’t ladder or fray at cut edges. Additionally, tricot fabric typically has different face and back textures, as noted earlier (smooth vs ribbed), whereas a single jersey has the knit-vs-purl face/back or a double jersey looks the same on both sides. The alignment of loops is also different: tricot’s face has visible wales (vertical columns of loops) and the back shows crosswise underlaps, while jersey’s face shows the loop Vs and the back shows loop curves.

Another structural telltale is edge behavior.

A cut edge of jersey will curl strongly (an inherent trait of stockinette-type weft knits). Tricot and other warp knits, on the other hand, lie much flatter when cut and resist curling. (There may be minor rolling if the tricot has tension, but nothing like the persistent curling of jersey.) This can be a practical advantage in cutting and sewing tricot fabrics – pattern pieces maintain their shape without edges rolling up.

In summary, warp-knit tricot vs weft-knit jersey differs in: the number of yarns used (many vs one), knitting direction (lengthwise vs widthwise loops), face/back appearance (different vs usually one smooth/one looped), and behavior when cut (tricot is stable and won’t unravel; jersey can curl and ladder). These structural differences underlie many of the property differences discussed next.

Stretch Direction and Elastic Recovery

One of the most important differences between tricot and jersey knit spandex fabrics is how they stretch. Tricot fabrics have a controlled stretch that is usually greater in one direction than the other. Specifically, a classic tricot warp knit stretches primarily in the lengthwise (warp) direction and has limited stretch in the width.

This is inherent to the zigzag loop structure: the loops can easily deform along the vertical axis of the fabric, but the horizontal stability (especially if no spandex is used) is quite high. By contrast, jersey knit stretches readily in both directions, thanks to the looped structure that can open up under tension. Even without any spandex, a cotton jersey will stretch a bit horizontally and vertically (more in width). When spandex is added to jersey, it typically becomes a true 4-way stretch material, meaning it can extend significantly in both the crosswise and lengthwise directions and snap back. Jersey with 5–10% spandex (often called Lycra® or elastane) can easily stretch 50% or more beyond its resting length and still recover.

Tricot fabrics often incorporate spandex as well (often 15–20%) to achieve 4-way stretch, especially for athletic and swimwear applications. Modern tricot knits with spandex actually do stretch in both directions – however, the knit construction still usually yields a firmer stretch in one direction and more power or resistance in the other.

For example, a nylon-spandex tricot used in swimwear might stretch 75% in the vertical direction but perhaps only 30–50% in the horizontal direction, giving it a supportive “snap-back” fit around the body. The stretch is controlled and has measurable modulus (power), which is great for compression garments that must maintain shape. Weft-knit jersey, on the other hand, generally has a softer, more yielding stretch – it can elongate easily (especially across the width) for comfort and movement. This makes jersey ideal for garments where flexibility and drape are key (like a flowing knit dress or a comfortable t-shirt).

When it comes to elastic recovery (the ability to spring back after stretching), both fabric types benefit from spandex. High-quality spandex blends have excellent recovery, preventing bagging or sagging of the fabric over time. However, even without spandex, warp-knit tricots tend to have better inherent recovery and dimensional stability than weft knits. The warp-knit structure means the fabric doesn’t permanently distort as easily – it “remembers” its original dimensions more effectively.

Jersey knits without spandex (like 100% cotton jersey) can suffer from growth (getting stretched out) or bagging at elbows and knees with wear. They rely on the yarn’s resilience, which is lower than that of a structured warp knit. In summary:

• Tricot fabric (warp knit) – engineered stretch with more in the vertical direction; very good recovery and shape retention (especially with spandex); provides controlled compression.

• Jersey knit (weft knit) – generous stretch in all directions (especially widthwise); with spandex it’s extremely elastic; tends to have a softer stretch and needs spandex for strong recovery to avoid long-term distortion.

Designers must consider these differences: For a garment that needs firm support and to hold a tight shape (e.g. shapewear or a sports bra), a tricot with specified stretch percentages is often used. For something like a casual stretch top or leggings that prioritize comfort, a spandex jersey is common for its easy stretch.

Fabric Weight (GSM) and Drape

Both tricot and jersey knit spandex fabrics come in a range of weights (measured in GSM – grams per square meter), but they often occupy different niches in terms of typical weight and how they drape. Tricot fabrics are frequently produced in medium to heavier weights for supportive apparel. For instance, a tricot used in swimwear or activewear might be around 180–200 GSM, providing sufficient opacity and durability.

Heavier tricot variants, like powernet (used in shapewear or compression garments), can be 200–300 GSM or more, offering very firm control. On the lighter end, there are also sheer tricot meshes and linings that are much lighter (some nylon tricot linings can be under 100 GSM and quite translucent). Tricot fabric can range from very sheer and lightweight to opaque and heavyweight, depending on knit density and yarn size. This versatility means tricot can be engineered to have a specific weight for the end use – lighter for lingerie and dancewear, heavier for swimwear and shapewear.

Jersey knit fabrics are also made in a wide weight range, but tend to be used at lighter weights for many everyday garments. A standard cotton or cotton-blend t-shirt jersey is often ~120–180 GSM (light to medium weight). Viscose or silk jerseys for dresses might be lighter (and drapier). On the other hand, double-knit jerseys (like ponte or interlock) can be medium to heavy (250–300 GSM) for more structured garments.

A polyester-spandex jersey for leggings or yoga pants often falls in the midweight category (~200–250 GSM) to ensure coverage and support. Heavier fleece-back jerseys for sweatshirts are even thicker. So jersey spans a big range, but as a rule, if you need a very heavy, strong knit (like for high compression), you’d likely choose a warp-knit tricot; if you need a ultra-light drapey stretch, a weft knit might be more common.

When it comes to drape, jersey fabrics are generally known for a soft, flowing drape whereas tricot has a controlled, structured drape. A thin rayon jersey, for example, will cling and flow over the body’s curves, creating a fluid silhouette. Even cotton jersey has some drape and tends to hang softly (though cotton is a bit more matte and structured than rayon or silk). In fact, most jersey fabrics have a nice drape, with smoother filaments (like viscose or silk) yielding an even more liquid drape, while cotton jerseys are slightly more body due to the fiber stiffness.

Tricot fabric, on the other hand, is often described as stable and not prone to billowing or bias-draping. The warp-knit construction holds the fabric somewhat more upright. Tricot will of course fold and bend (it’s still a knit), but it tends to “snap” back and not form deep bias drapes. This is advantageous in applications like swimwear or sportswear, where you don’t want the fabric growing or sagging out of shape. As one source notes, tricots have a sturdy handle and their construction prevents them from billowing or sagging, maintaining a consistent shape. That means a tricot leotard or swimsuit will keep its form-fitting silhouette even when wet or under strain.

In summary, weight and drape differences: Tricot is often used in medium/heavy weights for structured stretch garments and has a more controlled drape (fabric hangs smoothly and tautly). Jersey is commonly seen in light to medium weights for garments that benefit from softness and flow, offering a more relaxed drape (though heavier double-knit jerseys can provide structure too).

Both fabrics can be selected in various weights, but one should match the GSM to the end use: e.g., lightweight tricot mesh for a breathable lining vs. heavyweight cotton-spandex jersey for opaque leggings. Additionally, keep in mind that higher GSM usually means more opacity and support, which leads us to the next comparison.

Breathability and Opacity

Both tricot and jersey knit fabrics can be quite breathable, but their breathability often depends on fiber content and knit openness. Jersey fabrics (especially those made from natural fibers like cotton or blends) are known for being breathable and absorbent. A cotton jersey T-shirt, for example, is comfortable in warm weather because the knit allows air flow and cotton absorbs moisture, preventing a clammy feel.

Even polyester jersey for sportswear is usually knit in a way (sometimes with small mesh pores or moisture-wicking finishes) to encourage ventilation. Jerseys tend to have a bit more inherent “airiness” because the loops create tiny spaces in the fabric. That said, a tightly knit, high-quality jersey is usually fully opaque, with the loops packed closely enough that you can’t see through it.

The opacity of jersey fabric is a plus for things like T-shirts and leggings – a dense jersey will not let light through or show undergarments. Of course, if a jersey is very lightweight or made of a smooth filament (like silk jersey), it can be semi-translucent (silk jerseys are often a bit sheer with a sheen). Generally, though, one key characteristic of a good jersey for clothing is that it’s opaque and covers the body, despite being breathable and thin.

Tricot fabric can also be breathable, though it often uses synthetic fibers (nylon/poly) which are not absorbent.

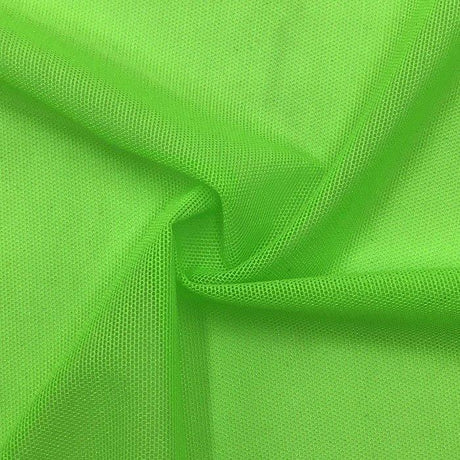

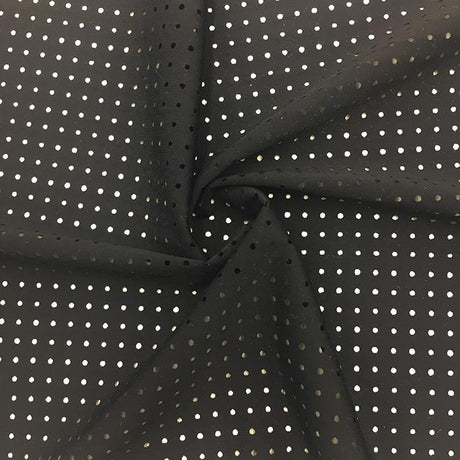

Instead of absorbing sweat, a nylon tricot will usually let moisture pass through or wick it to some extent. The knit structure of tricot can be engineered to enhance airflow – for example, there are tricot mesh fabrics or “warp-knit mesh” where certain needles are set to create small, regularly spaced holes for ventilation. Even a standard tricot, though, typically has interstices between yarns that allow air and water permeability.

One source points out that because of the way tricot is constructed, it offers good air and water permeability (breathability) while still being soft and drapey. Additionally, tricot fabrics can strike a balance between opacity and breathability, depending on yarn thickness and knit density – they range from slightly sheer to fully opaque in coverage. For instance, a 40-denier nylon tricot (commonly used in lingerie) might be semi-sheer and very breathable, whereas a heavier swimwear tricot with fine yarns knitted tightly will be opaque and still allow some air exchange without clinging to the skin. The non-clinging nature of tricot is an advantage in swimwear, as noted by one apparel guide: when blended with spandex, tricot offers breathability and a non-clinging fit with 4-way stretch, ideal for swimwear.

In practical terms, both fabrics can be made opaque enough for modesty or sheer for design effect. If you require absolute opacity (say for squat-proof athletic leggings or compression shorts), you would choose a higher weight or tighter-knit jersey or tricot. If you want some sheerness or ventilation, lightweight versions of either can be used (mesh jersey or mesh warp knits).

A difference might be that tricot, being run-resistant, can often use very fine yarns to create a stable sheer fabric (e.g., powernet or stretch tulle) that still won’t easily rip, whereas a very thin weft-knit can be more prone to running if snagged. For breathability, cotton jerseys excel due to cotton’s moisture absorption, while nylon tricot excels in moisture wicking (nylon doesn’t hold moisture, and if engineered with a finish, it can actively transport sweat away from the body).

Polyester jerseys and tricots both tend to dry quickly and allow air through, but polyester is slightly less breathable than nylon. To summarize: jersey knit spandex is generally breathable and opaque in normal clothing weights, and tricot fabric is also breathable (especially in open-knit or mesh constructions) and can be made sheer or opaque as needed. Designers often double up lighter tricots or add linings for opacity (for example, a swimsuit might use two layers of thinner tricot to ensure coverage), or choose a thicker jersey knit if using a single layer.

Texture and Softness

In terms of how they feel, jersey and tricot have distinct textures. Jersey knit is typically very soft to the touch, with a comfortable, slightly plush hand (particularly if made from cotton or other natural fibers). The right side of a single jersey is smooth and the back side has a faint ribbed or pebbled feel from the purl loops, but overall both surfaces are gentle on the skin. MasterClass’s fabric guide emphasizes that jersey is soft and smooth, providing comfort for the wearer. A cotton jersey has a matte, cozy softness (it can feel like a soft T-shirt or loungewear).

A rayon or silk jersey feels extra smooth and slinky. Even polyester or nylon jerseys can be made with a brushed finish to give a “peachskin” soft feel. When spandex is present, jersey often has a slightly cooler, elastic feel but still remains soft. One thing about jersey: if it’s a blend with polyester and not brushed, it might feel a bit slick or plastic-y compared to nylon. Nylon-spandex jersey tends to be softer and smoother than poly-spandex jersey, which can be a bit firmer. This is why some high-end leggings use nylon blends (for that silky smooth touch), whereas budget sportswear might use polyester blends (a tad stiffer but more cost-effective).

Tricot fabric, on the other hand, is often described as silky on the front side and slightly textured on the back. The technical face of tricot is very smooth and sleek, thanks to the fine filament yarns and the knit structure that presents closed loops on the surface. The back of tricot has tiny horizontal ribs or zigzag underlaps that you can feel if you run your hand over it – it’s not rough by any means, but you notice a faint texture compared to the ultra-smooth front. Overall, tricot is smooth and soft against the skin.

In fact, these fabrics are favored for intimate apparel and swimwear because they glide over the body without friction. A nylon tricot slip, for example, feels cool and slippery, which is ideal for layering under clothes. Modern tricot knits with spandex are often very soft as well – they mold to the body like a second skin. One textile source notes that tricot’s front is sleek and soft, making it perfect for garments like lingerie and activewear where you want that smooth, comfortable contact.

Tricot’s softness combined with its zigzag knit gives it a distinct feel that’s a bit different from jersey: you might describe it as “slicker” or silkier (especially if made of nylon) whereas jersey is “cozier” or cottony (if made of cotton).

In terms of surface appearance, jersey is usually matte (unless it’s a shiny fiber like some polyester jerseys or has a lustrous finish). Tricot can have a slight sheen on its smooth side, particularly with nylon or polyester filaments – for instance, many swimwear tricots have a subtle shine or a “semi-matte” glimmer. There are also tricot variations like satin tricot that are deliberately shimmery. This can affect perceived softness (shiny synthetics might feel slick). Meanwhile, jersey’s appearance can vary widely (from heathered cotton knits to printed poly jerseys), but when people think of jersey, they often think of that soft, matte knit that drapes nicely.

To summarize, both fabrics are soft, but in different ways: Jersey knit (especially cotton or rayon jersey) gives a soft, cushy feel and often a bit of fuzz or yield that feels cozy on the body. Tricot fabric provides a smooth, cool touch – it’s the kind of softness you find in fine lingerie or quality swimwear, hugging the skin gently without irritation. Neither fabric is inherently scratchy (unless low-quality fibers are used).

If anything, the softness will depend more on the fiber blend: for example, a nylon-spandex tricot is usually very soft and smooth (nylon is known for its silky hand), whereas a 100% polyester jersey might feel a little rougher or more synthetic. Designers will choose fiber content accordingly: nylon/spandex for a soft luxe feel in activewear or intimates, cotton/spandex for a breathable soft feel in casual wear, etc.

Durability and Stability

Durability refers to how well the fabric holds up to wear, stress, and washing, while stability refers to maintaining shape and not distorting. Here, tricot warp-knit fabrics have a clear advantage in many respects. The construction of tricot makes it highly durable and resistant to runs or unraveling.

If you cut a tricot fabric, the edges will not fray and the loops won’t start pulling out. This is a huge benefit for lingerie and athletic wear, where you don’t want a small cut or hole to turn into a major run. One source explicitly states: Tricot is more durable and resistant to unraveling, maintaining its shape when stretched, whereas weft knit fabrics (like jersey) are more prone to unraveling or distortion if pulled. Tricot’s dimensional stability means even after repeated stretching or after washing, it tends to retain its original shape and size much better than a weft knit would. That’s one reason warp knits are often used in high-performance or industrial applications – they don’t shrink or skew as easily.

Jersey knit fabrics, especially those in lower weights or made of natural yarns, are typically less durable in the long run. Because a jersey is one continuous yarn, a small break can cause a “ladder” (think of a run in a knitted sweater or a pair of stockings – though stockings are often warp knit, a similar concept of a run applies).

In everyday jerseys like T-shirts, this isn’t usually a big issue, but if you cut a jersey and don’t secure the seam, it can unravel along the cut edge until it hits a seam. Jersey fabrics can also be prone to pilling (forming little fuzz balls on the surface) if the fibers are short or soft (cotton and polyester blends often pill over time).

Warp-knit tricots, using filament yarns, are generally resistant to pilling – their smooth surface doesn’t fuzz up easily, and some are specifically finished to resist abrasion. In fact, tricot is known for being snag-resistant and run-resistant; one swimwear fabric guide notes that tricot is “resistant to snags and runs, combining softness with incredible durability”. That means it can handle the rigors of activities (like rubbing against pool edges or repeated stretching) better without getting damaged.

When considering longevity, a well-made nylon tricot may outlast a similar-weight jersey in a demanding use case. For example, a pair of compression shorts made of warp-knit fabric will likely hold its compression level and not tear as easily as a pair made of weft-knit jersey. On the flip side, jersey fabrics can be very durable in their own right if constructed well (think of heavy interlock knits or double jerseys used in sports uniforms – they can last years). But for the same weight, warp knits often have higher tensile strength and tear resistance. Also, warp knits often can achieve strength while being lighter.

Dimensional stability is another aspect: Jersey knits can sometimes suffer from distortion – e.g., a T-shirt might twist after laundering if the knit wasn’t properly stabilized or if cut off-grain. Warp knits are usually very stable in dimension (one reason they’re used as lining or backing fabrics).

They won’t generally skew or torque. Additionally, warp knits resist edge curling and maintain clean edges which is a form of stability in cut-and-sew operations.

In short, tricot fabric offers excellent durability and shape stability, not fraying or laddering and holding up under stress. Jersey knit is very durable for everyday wear but is relatively less stable – it can unravel if not hemmed, edges curl, and it may lose shape without added elastic fibers or structural support. This doesn’t mean jersey is “bad” – many jerseys (especially with spandex and good quality fibers) are plenty durable for their intended use. It just means that if you need a fabric that must endure high tension or long-term use (say, a compression garment or a net fabric for sports gear), a warp knit is often chosen.

Notably, many shapewear and medical compression fabrics use warp-knit powernet for its strength and recovery, and many sports bras have warp-knit stabilizer panels where durability is critical.

Fiber Composition and Its Impact

Both tricot and jersey can be made from various fiber compositions, and this choice greatly affects the feel and performance of the fabric. Here are some common compositions and their implications:

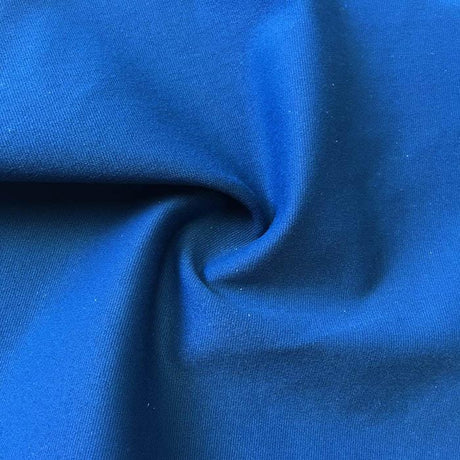

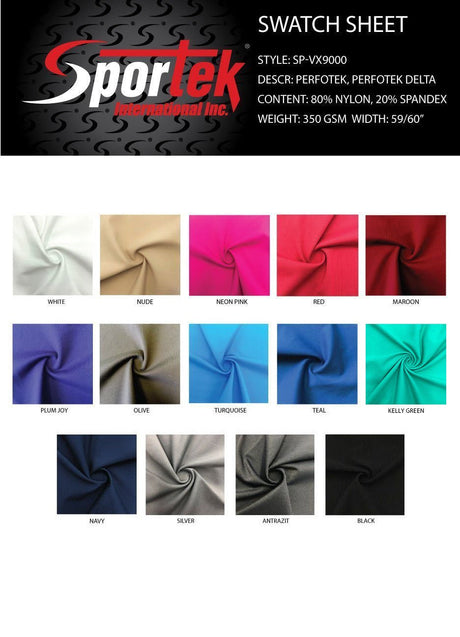

• Nylon (Polyamide) + Spandex: This is very common for tricot fabrics (e.g., 80% nylon, 20% spandex for swimwear) and also used in some high-end jersey knits (like certain yoga pants). Nylon-spandex fabrics are generally softer and smoother than polyester-spandex. Nylon has a very silky hand and high strength.

It also has good moisture-wicking ability (though it can absorb a small amount of water compared to polyester). In use, a nylon-spandex tricot fabric will feel soft, have a slight sheen, and be extremely strong – ideal for swimwear, intimates, and compression garments. Nylon is also quite elastic and resilient, contributing to the fabric’s recovery. For jersey, nylon blends are less common (since nylon is more expensive than polyester or cotton), but when used, they give a nice smooth stretch fabric (for example, some hosiery or lightweight athletic jerseys are nylon-based for a second-skin feel, similar to tricot).

Nylon does tend to be slightly less UV resistant than polyester (it can yellow or weaken with prolonged sun/chlorine exposure), but many swimwear-specific nylons are treated for this. Overall, nylon-spandex is a premium blend known for durability, softness, and high stretch.

• Polyester + Spandex: This blend is extremely common in jersey knits for activewear (think of the typical sports leggings or printed athletic knit tops) and also used in some tricots (certain swimwear or lingerie fabrics use polyester instead of nylon).

Polyester-spandex fabrics are typically more affordable and have excellent color retention – polyester holds dye well and is more UV/fade resistant than nylon. Polyester also doesn’t absorb water, which means poly/spandex fabrics dry very quickly (great for swimwear and athletic shirts). However, polyester has a slightly firmer hand – it’s not quite as naturally soft as nylon. A poly-spandex jersey may feel a bit slick or cool, with a matte finish in many cases (poly tends to have less sheen than nylon).

It is also slightly more prone to pilling, but when blended with spandex and high-quality filaments, it can still be quite smooth. Polyester-spandex tricots are known for their durability and resistance to chlorine (making them good for competitive swimwear), and they often have a matte look. The key differences: nylon gives more softness and stretch, polyester gives more robustness against the elements (and usually costs less).

Designers choose poly/spandex when they need a strong, colorfast fabric (e.g. printed leggings that shouldn’t fade) or a bit more structure. One note: poly can sometimes feel less breathable (it’s not absorbent at all), but modern moisture-wicking poly jerseys are engineered to move sweat to the outer surface where it can evaporate.

• Cotton + Spandex: This is a common jersey knit composition for things like casual wear, underwear, and some athletic wear. Cotton brings a very soft, natural feel and high breathability/absorbency, while a small amount of spandex (5–10%) adds stretch and recovery. Cotton-spandex jerseys are beloved for t-shirts, yoga tops, and leggings where comfort is king.

They tend to have a matte, cottony look and feel. The downside of cotton/spandex is that cotton holds moisture (so it’s not ideal for really sweaty activities or swimming) and can shrink or lose shape a bit more over time compared to synthetics. You won’t typically find cotton in tricot fabrics – since tricot machines use filament yarns, cotton (a staple fiber yarn) isn’t commonly warp-knit, and also cotton lacks the strength when that thin. So cotton is basically a jersey domain.

Cotton jerseys are highly breathable and skin-friendly, but not as durable as synthetics in intense use. Designers might choose a cotton-spandex jersey for a line of casual leggings or tees, but would not use it for say, a structured swimsuit or long-life activewear, where nylon/poly would perform better.

• Rayon or Modal + Spandex: These are also for jersey knits mostly. Viscose rayon or modal can make jersey incredibly drapey and cool to the touch. They are cellulose-based fibers, very soft (often softer than cotton) and lend a luxurious drape. However, they have low recovery (hence spandex is needed) and can be less durable when wet. These jerseys are great for fashion tops and dresses where a flowing drape is desired. They’re less common in performance wear due to durability issues.

• Fiber content in tricot variations: Aside from nylon and polyester, tricot can be made with things like acetate or even blends including cotton or viscose, but these are specialty cases (acetate tricot linings, etc.). Most often, if you have a tricot fabric in your hand, it’s likely nylon or polyester based. Some modern warp knits blend in natural fibers or finishes to simulate a cottony feel, but the core of tricot for stretch applications is synthetic filaments plus elastane for stretch.

The feel and performance summary: Nylon-spandex tricot – ultra-smooth, strong, good stretch, used for high-end applications. Poly-spandex tricot – strong, slightly firmer hand, very colorfast, used for athletic and swim when cost or printability is a factor. Cotton-spandex jersey – soft and breathable, but holds moisture; great for comfort, not for high compression. Poly-spandex jersey – durable and wicking, a bit less soft; used in tons of sports apparel. Nylon-spandex jersey – less common, but very soft and high-performing (e.g. some seamless athletic wear).

Knowing these differences, a designer might choose tricot fabric with nylon/spandex for a swimsuit to get that smooth feel and strength, or a poly/spandex jersey for a printed sport legging to ensure the print stays vivid and the fabric withstands abrasion. Fiber affects not only feel but also things like drying time (poly/nylon dry fast, cotton slow), opacity (cotton can be more opaque for a given weight due to its fluffiness), and care (poly/nylon don’t shrink, cotton/rayon can). All these factors tie back into choosing between tricot and jersey as well, since fiber and knit type together determine the final properties.

Common Applications in Apparel

Both tricot and jersey knit fabrics are used across various apparel categories, sometimes for different roles. Here we compare their usage in key applications, highlighting why one might be chosen over the other:

• Swimwear: Tricot is almost synonymous with swimwear fabric. If you pick up a competitive swimsuit or a bikini, chances are the outer fabric is a warp-knit tricot of nylon/spandex. The reason is tricot’s strength, controlled stretch, and chlorine resistance (especially in poly blends). Tricot swimwear fabric provides a snug fit that doesn’t bag out when wet and can withstand the tension of movement and water. It also resists runs – a critical factor, as a run in a swimsuit could be disastrous.

Additionally, tricot’s smooth surface is great for printing vibrant patterns or achieving a sheen. Many swim tricots have a matte or shiny finish and offer 4-way stretch for comfort. Jersey knit is less common as a swimwear shell fabric, though it’s not unheard of. Some rashguards or swim shirts might use a circular-knit jersey (often polyester jersey) because it has a bit more drape and looks like a normal fabric while still being swim-rated.

However, those are usually called “swim jersey” but are often a specialized warp-knit as well. Generally, designers choose tricot fabric for swimwear – from one-piece suits to bikinis – due to its proven performance in water. Jersey might appear in swimwear as lining (for example, a lightweight poly jersey lining in swim trunks) or in less structured fashion swim pieces, but it’s not the industry standard for serious swim garments.

• Activewear and Sportswear: Both fabrics see heavy use here, but in different garment types. Leggings and yoga pants can be made from either warp-knit or weft-knit fabrics. Many high-compression or “performance” leggings use a warp-knit (sometimes marketed as “tricot knit”) because it gives a supportive feel and doesn’t become see-through (often 75% nylon, 25% spandex tricot, for instance).

These can feel a bit more compressive (think of leggings that suck you in). On the other hand, plenty of popular leggings are made from polyester or nylon spandex jersey knits, which are soft and stretchy – these might have a brushed feel (as with many yoga leggings) for comfort. The choice often comes down to desired compression and aesthetic: a tricot legging fabric with high spandex content provides strong compression for functional sportswear, while a jersey knit legging might be chosen for athleisure where comfort is key. Sports bras frequently utilize warp knits (tricot or mesh) in certain parts – for example, powernet tricot panels for extra support or a tricot lining that doesn’t stretch as much (to hold the bust in place). The outer layer of a sports bra could be jersey for design, but the inner layer might be tricot for strength.

Athletic tops and tees are usually jersey knits (poly or poly blends) because they are light, breathable, and drapey for ease of movement. Running shirts, football jerseys (the generic term), and training tops are typically made from circular-knit jerseys, some with mesh textures, but still weft-knit. Track pants or shorts can be jersey (like the classic mesh basketball shorts which are actually warp-knit mesh, interestingly, or sweatpants which are jersey fleece) or tricot (certain training jackets use a tricot fabric with a bit of shine, often called “tricot track jackets”).

In fact, the term “tricot” is sometimes used to describe those satiny track jacket fabrics. Those are warp-knit and chosen for their smooth face and somewhat wind-resistant structure. In summary, activewear uses tricot for high-stress, supportive components (swimwear, compression leggings, sports bra liners) and jersey for looser, comfort pieces (t-shirts, base layers) – though there is crossover and both can be used creatively in a single garment.

• Intimates and Lingerie: Tricot has a long history in lingerie. Classic nylon tricot fabric was used for decades in making slips, panties, nightgowns, and bra linings – it even has that vintage connotation of silky lingerie. The smoothness and lightweight strength of tricot make it ideal for delicate undergarments that still need durability.

For example, many bras use a nylon tricot as the cup lining or as the band fabric, because it’s supportive and non-stretch in one direction (providing support) and softly stretchy in the other (for comfort). Powernet tricot (a stronger, open variant) is used in shaping lingerie or the backs of bras for extra firm control. Panties can be made of tricot – especially the satiny styles or those “granny panty” 100% nylon briefs from years past were tricot knit (hence they were semi-sheer but very strong and non-run).

Jersey also appears in intimate apparel, particularly for more casual or comfort-focused items: e.g., cotton-spandex jersey is common in women’s underwear and men’s underwear, because it’s breathable and soft. Many panties have a cotton jersey gusset for hygiene. Bralettes and lounge bras might be made from cotton or modal jersey to feel comfy (essentially like a crop-top). So in lingerie: use tricot fabric for a polished, supportive, and durable structure (silky slips, bra power mesh, etc.), and use jersey for everyday softness and stretch (cotton knit panties, stretch knit bralettes).

High-end lingerie often combines both: for instance, a bra might have cups in a rigid tricot and the side panels in a powernet tricot, but the brief might have a cotton jersey front for comfort and a lace (warp-knit lace) back for aesthetics. The technical audience will note that warp knits (tricot and raschel lace) dominate the foundation garment segment for their function.

• Dancewear and Costumes: Dance and performance garments (like leotards, unitards, gymnastics costumes, figure skating dresses) require fabrics that move with the body but also hold up to strain. Tricot spandex fabrics are commonly used in these outfits, often under names like “milliskin tricot” (a popular nylon-spandex tricot with a smooth finish) in the cosplay and dance community.

These fabrics have good 4-way stretch, come in lustrous or matte finishes, and allow for a tight fit that shows off the body lines (important in dance). They also tend to not become see-through when stretched, if of good quality. Jersey knit fabrics can be used in dancewear for items like practice dance clothes or looser pieces – for example, some modern dance or yoga wear uses rayon jersey for flow.

But when it comes to the classic leotard, warp-knit tricot or similar is king because it gives that second-skin fit and sheen. Additionally, raschel warp knits (a cousin of tricot, often used for lace or mesh) appear in dance costumes for decorative overlays or mesh cutouts. Weft-knit jerseys might show up as well in costumes (say, a stretch velvet which is usually a knit pile on a jersey base), so both knit types can be present. Yet, if one is making, say, a ballet leotard or skating costume, a warp-knit tricot is usually the top choice due to its combination of stretch and stability (no wardrobe malfunctions on the ice, please!).

• Shapewear and Compression Wear: This is a domain where warp-knit fabrics (tricot, powernet, etc.) are heavily favored. Shapewear (think of girdles, slimming shorts, waist cinchers) needs to exert significant compression on the body. Powernet tricot fabrics are designed for this – they use high denier nylon with a lot of elastane and a fairly tight knit structure to create a fabric that can stretch to encase the body but strongly pull back to shape it. Such fabrics might only stretch, say, 50% of their length but require a lot of force to do so, thus smoothing and “holding in” the wearer.

Weft-knit fabrics would have a hard time achieving that level of modulus without either being uncomfortably thick or losing shape. Therefore, the panels in firm-control shapewear are almost always warp knits. Even in medical compression garments (like compression stockings, surgical compression wear), warp knitting is used to precisely control elasticity. Jersey knit (especially if double-knit) could be used for lighter compression or support – e.g., some mild shapewear or athletic compression gear might use a tight interlock jersey. But for serious compression, warp knits rule.

Designers choosing fabric for shapewear will pick a tricot or similar warp fabric for its durability under high tension and consistent pressure on the body. They might incorporate a jersey lining for comfort or a brushed feel, but the power layer is warp knit.

In summary, tricot fabric shines in applications requiring strength, controlled stretch, and stability: swimwear, performance activewear, lingerie foundations, dance costumes, and shapewear all rely on tricot’s technical advantages. Jersey knit excels where comfort, flexibility, and drape are desired: casual apparel (t-shirts, jerseys, leggings for everyday), loungewear, base layers, and absorbent garments. Often, the two fabrics complement each other – for example, a garment can use tricot in one panel and jersey in another, or a designer might prototype in a jersey and then move to a tricot for production to get the needed performance.

Identifying Tricot vs Jersey: Tips and Tests

For those in the textile industry or fashion design, being able to identify a fabric as tricot or jersey knit is important. Here are some technical clues and simple tests to distinguish the two:

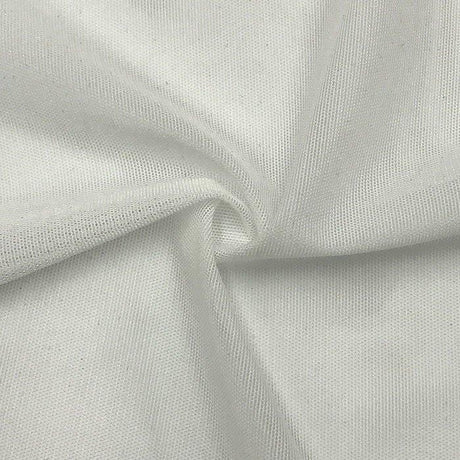

• Face and Back Appearance: Examine the fabric’s right and wrong sides. Tricot fabric typically has one side that is smooth with fine vertical wales (you might see very tiny lengthwise lines or just a uniform smooth field) and the opposite side has horizontal zigzag ribs or floats that give a slight texture. If you gently stretch the tricot, on the smooth side you might discern a faint stripe pattern vertically, and on the back you’ll see tiny chevron or zigzag patterns.

Jersey knit, in contrast, usually has a distinct knit vs purl side: the front will show tiny V’s (knit stitches) aligned in columns, and the back will show small semi-circular loops (purl stitches) in rows. If it’s a double-knit jersey (interlock), both sides may look like knit Vs (smooth), which could confuse things – but an interlock is thicker and doesn’t curl at edges, another clue. In general, if both sides of the fabric look identical (and it’s a single layer), it’s likely a double-knit (weft) or something special. If one side is clearly different (especially one shiny/smooth and one dull/textured), it leans toward warp-knit tricot.

• Stretch Test: Hold the fabric and stretch it lengthwise and widthwise. Note the stretch and resistance. Tricot fabric often stretches more (or more easily) in one direction – usually the length. For instance, you might feel a strong pull and snap-back vertically, but much less give horizontally (some tricot even feels almost stable across the width). Jersey knit tends to stretch fairly easily in both directions, with perhaps a bias to stretching more in width. If the fabric stretches a lot and roughly equally up-and-down and sideways (especially if it has spandex), it could be a jersey.

If it has a weird property of stretching a lot one way and being quite firm the other, that’s a hallmark of warp knit (unless it’s a rib knit, but rib knit looks ribbed on both sides which is a different beast). In summary, more 2-directional (anisotropic) stretch = likely tricot; more uniform 4-way stretch = likely jersey. This isn’t foolproof, but a clue. Also, observe recovery: warp knits snap back quickly and firmly, jerseys with spandex do too, but a jersey without spandex might sag a bit after stretching.

• Edge Behavior: Cut a small swatch or find a raw edge. Jersey knit edges will curl notably – along the cut edge, a single jersey curls toward the knit (right) side horizontally and toward the purl (wrong) side along the length (selvage). This means a cut edge will roll up on itself, making a little tube, which is a dead giveaway of single jersey. Tricot edges, when cut, generally lie flat without significant curling.

You might see a tiny roll or nothing at all. Also, check if the edge frays or unravels: if you start to pull at a cut edge of jersey, you might be able to pick off a yarn that will cause a whole row of loops to undo (you’ll see a ladder forming). With tricot, picking at a cut edge usually does nothing – it won’t fray or come undone easily. This difference in fraying/unraveling is a key identifier in the lab: weft knits can be unraveled along a course, warp knits cannot.

• Look for the “Zigzag” or “V” Patterns: With a magnifier or just keen eyes, look closely at the fabric structure. On one face of a tricot, you might discern tiny zigzag lines (especially if you stretch it slightly – the underlap threads show as diagonal lines connecting wales). On a jersey face, you’ll see V shapes (loops) in a grid. On the back of a tricot, look for sideways lines (almost like a tiny brick layout of yarn).

On the back of a jersey, look for round loop shapes. These visual cues require some familiarity, but once you’ve seen examples, it becomes easier. Many fabric books show microscope images of warp vs weft knits that highlight this difference.

• Feel and Sound: This is more subjective, but sometimes a tricot fabric made of filament yarn has a very smooth, cool hand and even a slight “swish” sound when rubbed (like silk). Jersey, especially cotton jersey, feels warmer and plushier by comparison. If you crumple the fabric in your hand, a thin tricot might spring back and feel a bit springy, whereas a cotton jersey will stay a bit wrinkled and feel like a T-shirt. Also, if you tug the fabric in two directions at once (bias stretch), a jersey might deform easily, whereas a tricot is tougher to distort off-axis (due to those inelastic underlaps).

Using these clues together helps. For example: you have a mystery fabric from a supplier – it’s smooth on one side, fuzzy on the other, curls on cut, stretches a lot in all directions but a tad more in one, and a pulled thread causes a run across the fabric. Those signs would weigh towards weft-knit jersey. Another fabric: smooth and slightly shiny on front, fine horizontal lines on back, stretches mostly one way, edges don’t curl or fray – that is likely tricot fabric. If still unsure, consider the context: If it came from a swimwear vendor, it’s likely tricot; if it’s from a T-shirt mill, it’s jersey.

Choosing Between Tricot and Jersey: Practical Tips for Designers

Deciding whether to use a tricot or a jersey knit spandex for a project comes down to the performance needs and characteristics desired. Here are some practical considerations for designers and manufacturers:

• Stretch and Fit Requirements: Determine how much stretch and what kind of recovery the garment needs. If you need high compressive force or support (e.g., shapewear, athletic compression, structured swimwear), a warp-knit tricot with controlled stretch is often the better choice. Tricot can be engineered to exact stretch percentages and power, ensuring the garment holds the body in. For garments that need maximum flexibility, drape, or comfort stretch, a jersey knit may be preferable as it generally offers more give. For example, yoga apparel that you want to feel like a second skin might use a soft jersey with spandex for that 4-way stretch and gentle recovery. Always check the stretch percentages: you might find something like “tricot 50% stretch lengthwise, 20% widthwise” vs “jersey 75% in both directions” and choose accordingly.

• Appearance and Surface: If you desire a smooth, slightly lustrous look, tricot fabrics often provide that finish (common in dance costumes, swimwear, satin-look athleisure). If you want a matte, cottony or heathered look, jersey is easier to source in those appearances (like a cotton-poly heather knit for athleisure). Tricot typically comes in solid colors with a uniform appearance; printing on tricot yields sharp results because of the smooth surface.

Jersey is also printable (sublimation or screen prints on poly or cotton jerseys are routine), but very lightweight jerseys can sometimes have print show-through. Consider also texture: if you want to avoid any chance of a fabric “catching” or causing friction (say, for a lining that should let outer fabric glide over it), tricot’s slick face is ideal. If you want a fabric with a bit more texture or thickness (like a knit that feels substantial for a jacket or top), a double-knit jersey or ponte might be more suitable.

• Durability and Use Case: For garments that will undergo heavy strain, frequent use, or need longevity, lean toward tricot or other warp knits. As one textile source advises, warp knits excel in stability and durability, while weft knits prioritize stretch and comfort (i.e., warp for strength, weft for elasticity). So for a long-distance running compression sleeve – warp knit. For a casual stretchy top – weft knit. Additionally, consider environmental exposures: chlorine, UV, saltwater – these are scenarios where a polyester-spandex tricot might outperform a jersey in retaining shape and color. Conversely, for everyday wear that gets lots of laundering, a cotton jersey might be perfectly fine and even preferred by consumers for its comfort despite not lasting as many years as a synthetic tricot.

• Manufacturing Practicality: Think about sourcing and production volume. Warp-knit tricot fabrics are often custom-produced and may have higher minimums (MOQ) for mills to run. If you are a small designer needing just a roll or two of fabric, you might find a wider variety of off-the-shelf jersey knits available in small quantities. Jersey is produced in huge quantities for the fashion market (for example, one can easily source cotton or poly jerseys in dozens of colors with low MOQ).

Tricot, especially specialized blends for swim/dance, might require ordering from a specialty mill or supplier with larger yardage. Plan for that if your design specifies warp knit. On the production line, note that jersey’s curling edges can make cutting and sewing more challenging – you may need to budget time for stabilizing edges or use techniques to handle curling when stitching seams. Tricot, not curling and not fraying, can often be cut and even left unhemmed in some applications (some athletic wear uses raw-cut warp knit edges because they stay neat). This could simplify finishing. However, sewing tricot (especially slippery nylon tricot) requires careful control as the fabric is slick – using the right needles and possibly a walking foot.

• Comfort and End-User Preference: Consider the end user. For instance, if the garment is meant to be worn all day (like underwear or casual leggings), comfort is paramount and a soft jersey might be more appreciated (e.g., cotton underwear breathe better than a polyamide shaper, though the latter shapes better). If the garment is for athletic or swim use, users expect the slightly tighter, smoother feel of warp knit (like a swimsuit or compression short). Also think of climate: a cotton or bamboo jersey might be better in hot weather for breathability, whereas a tricot might feel clammy unless well-ventilated because it doesn’t absorb sweat (though it can wick it). Many sports designs solve this by combining fabrics – e.g., a jacket with a tricot front for wind resistance and a jersey knit back panel for ventilation.

• Design Detailing: If your design calls for certain cut styles or embellishments, the fabric choice matters. For example, if you want laser-cut holes or edges that don’t need hemming (perhaps in a sports legging or a decorative pattern), a warp-knit tricot or spacer fabric is suitable since it won’t fray (some call these “free-cut” fabrics). A jersey would unravel or at least curl terribly if cut into lots of little holes.

On the other hand, if you plan to incorporate gathers or pleats in a knit garment (say a fashion top with ruched sides), a softer jersey might drape into pleats more gracefully than a springy tricot. Also, printing: if you need a digital print on a complex design, ensure the fabric selected can be printed with that method (most poly jerseys and tricots can be dye-sublimated with vivid results; nylon requires different printing methods or stock dyeing).

• Cost and Availability: Generally, jersey knits (especially cotton or poly) are more readily available and often cheaper per yard than high-quality tricot. Warp knitting is a more specialized manufacturing method with perhaps fewer suppliers globally, whereas jersey knits are made everywhere. If budget is a constraint and the project can tolerate either, jersey might be the economical choice. However, keep in mind the performance trade-offs – a cheaper fabric that fails in use is worse than a pricier one that succeeds. Sometimes you can find close equivalents in either category, so research both: for example, there are some modern circular-knit fabrics that mimic powernet (by using high spandex and tight interlock structure) – these could serve if warp knit isn’t available, though not always as well.

In many cases, the decision isn’t strictly one or the other; designers use a combination. A prime example is a competitive swimsuit: it might use a tricot fabric for the outer layer (for strength and opacity) and a thin jersey mesh lining at the gusset for a soft feel. Or an active legging might have a printed jersey body and panels of powernet tricot behind the knees for extra compression or style contrast. By understanding the distinct qualities of tricot fabric vs jersey knit, you can intelligently place each in a garment where it plays to its strengths.

Conclusion

Tricot and jersey are both essential knit fabrics in the world of stretch apparel, each excelling in different arenas. Tricot fabric, a warp-knit, provides superior stability, durability, and controlled stretch – it’s the technical workhorse for everything from swimsuits that must endure chlorine and tension to shapewear that sculpts the body, all while remaining smooth and comfortable. Jersey knit, a weft-knit, offers versatility, softness, and balanced 4-way stretch, making it the go-to for garments that prioritize comfort, drape, and ease. By understanding their structural differences – warp vs weft, zigzag vs loop – and comparing properties like stretch direction, weight, breathability, and feel, designers can make informed choices on which to use for a given project.

In summary, use “tricot fabric” when you need a strong yet flexible backbone for a garment – one that won’t easily run, will maintain its shape, and give firm but comfortable support (think high-performance activewear, lingerie, or swim). Opt for jersey knit when you desire softness, fluid movement, and everyday wearability – perfect for casual wear, base layers, or any design where the wearer’s comfort and range of motion are key. Both fabrics can incorporate spandex for excellent elasticity and recovery, and both come in a range of fiber blends (nylon, polyester, cotton, etc.) to fine-tune qualities like moisture wicking or hand feel. Ultimately, the differences between tricot and jersey knit spandex are a toolkit for the apparel professional: by leveraging these differences, one can create garments that not only look great but also meet the specific functional demands of their intended use.